Ocean Alliance Develops New Use for Drones in Whale Research: Non-invasive Tagging

Snotbot’ creators develop new use for drones in whale research

Snotbot’ creators develop new use for drones in whale research

The second in a trilogy of articles on innovative drones for conservation. Explore the first article, on drones saving island ecosystems here.

All images courtesy Ocean Alliance.

By DRONELIFE Features Editor Jim Magill

Ocean Alliance, the scientific research and conservation group that pioneered the use of UAVs in the study of whales with its breakthrough “Snotbot” technology, is finding a new way to use drones to learn about the underwater lives of these magnificent marine animals.

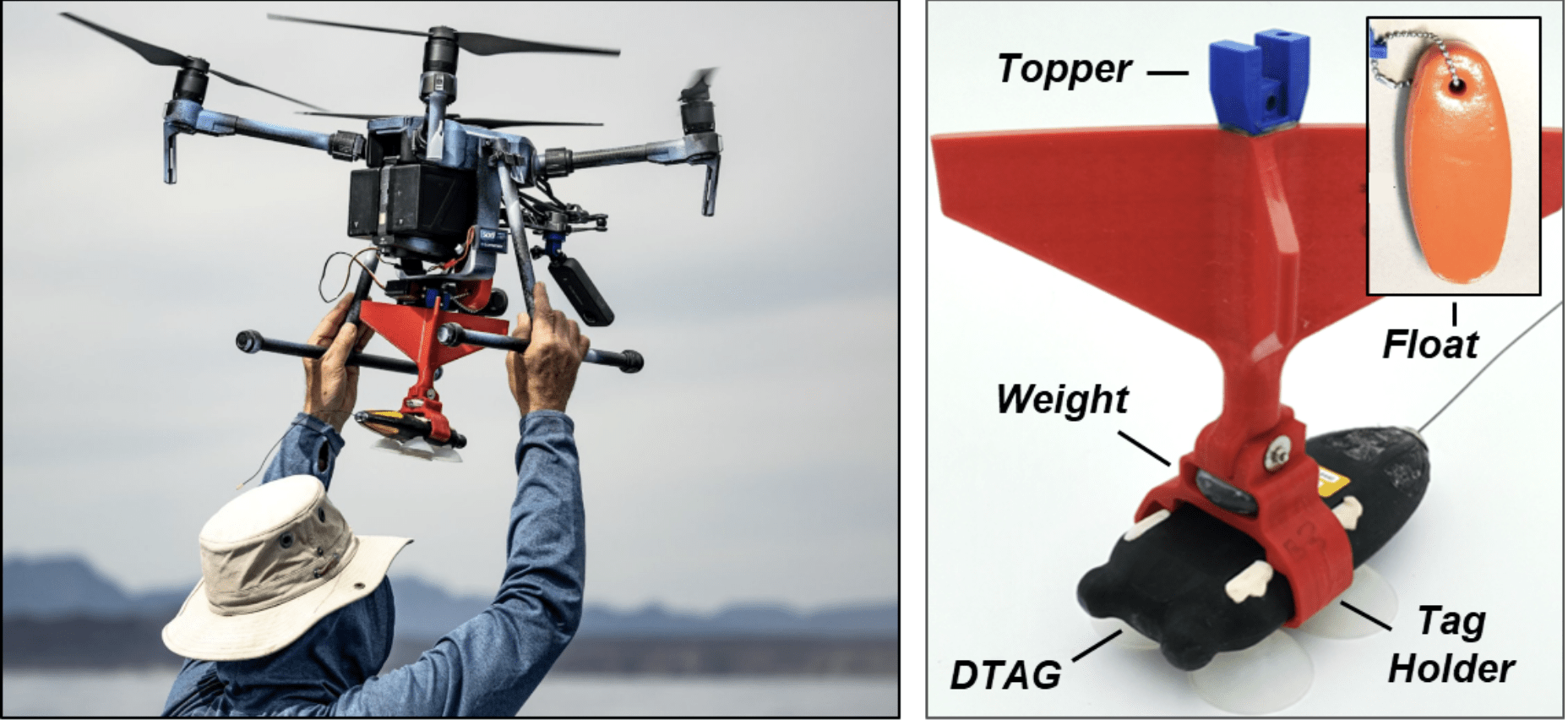

Since 2022, the Gloucester, Massachusetts-based non-profit organization has been using commercial DJI drones to tag whales with data-collecting sensors, which allow scientists to study the whales’ movements and behavior. Using UAVs to deliver the tags replaces older tagging methods, involving chasing the large mammals in boats and using long poles to attach the tags to the whale’s skin.

Andy Rogan, Ocean Alliance’s science manager, said the pole-tagging method has proved to be invasive for the whales and hazardous for the humans involved. “Whenever you’ve got a small boat next to an animal that size, it’s potentially dangerous,” he said.

“The problem with tags was that they were difficult to deploy,” Rogan said. “You needed to get right up close to the whale and essentially the tag was fixed loosely to the end of this long pole and then using the pole, you’d almost dunk the tag onto the whale and the whales didn’t like it.”

So, the Ocean Alliance team began experimenting with using UAVs to deliver the tags. The organization had already gained a great deal off expertise in the use of drones in its study of whales through its Snotbot program, in which it would fly a drone through the spray shot out of the whale’s blow hole, collecting biological samples.

“Within that sample — snot as such — there is all of this biological information, there’s genetic information, which is hugely important for understanding and managing whale populations,” Rogan said.

Based on the success of the Snotbot program, Ocean Alliance began looking at other potential applications for drone technology in the study of marine mammals. The result has been the drone tagging program, which since has become its principal focus.

Sensor-equipped tags have been used as a non-invasive way to study whale biology for about a quarter century. “Essentially these tags are almost like a Fitbit or a smart watch for a whale, and they allow us for the first time to understand what whales are doing when they’re underwater,” Rogan said.

“These tags just opened up a whole new world of whale science. They provide a really broad scope of data: on feeding ecology, on biokinetics, on acoustics, social communication, feeding, all of this really important stuff.”

Ocean Alliance went to work to establish a drone-based tagging program in late 2021. Working out of a rented warehouse north of Boston, the team developed the techniques it would use to position the drone above a whale that had come to the surface, and to drop the suction cup-equipped tags onto the whale’s skin. By February 2022, the team was ready to test its techniques in the field.

“We first actually deployed tags in February 2022 on blue whales and fin whales in the Gulf of California in Mexico,” Rogan said. “You can do all the testing you want in a lab setting and a controlled setting, but it’s very different when you’re out there on the ocean with whales. Our hope was to deploy 10 tags on whales during the expedition, which we thought was quite an ambitious target. And we ended up getting 21 on. So, it was a hugely successful expedition in the end.”

Although Ocean Alliance had previously worked in collaboration with Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts, to custom-design drones for its work, the group currently relies on commercially produced drones, chiefly DJI models.

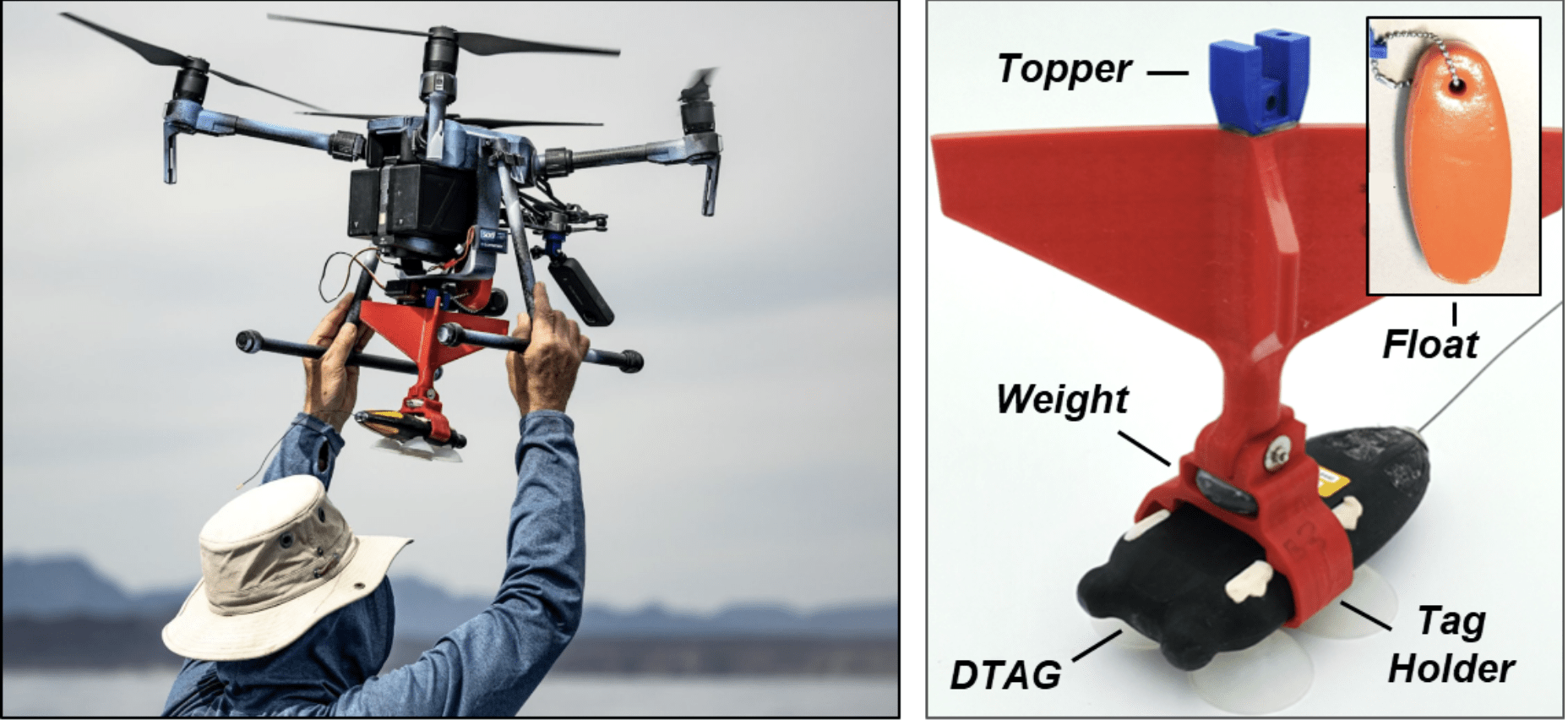

“Our workhorse is the DJI Inspire 2. But we also now have used some of the Matrice drones, and so we have the M210,” Rogan said. Using 3D-printed materials the researchers have engineered a propriety system for deploying the tags, which can be installed on the commercial drones.

The unit is able to carry and deploy a so-called D tag, or a data tag, the main kind of tag used by whale scientists around the world. Small and lightweight, the tag uses suction cups to attach to the whale’s skin. The tag adheres to the whale, collecting data, for about 24 hours, before it detaches and floats to the surface where it emits a radio signal, which allows it to be located and retrieved by the scientists.

In the initial experiments the tags would wobble too much after being dropped to allow the tags to properly attach, particularly if they were being deployed by a drone from an altitude of about 20 feet. So, the team designed and 3D-printed a dropper, similar to a lawn dart, which stabilizes the vertical fall, allowing the tag to be in the correct position to adhere to the whale.

When deploying heavier camera-equipped tags, known as CATS [Customized Animal Tracking Solutions] tags, the drone pilot allows the UAV to descend to a lower height, about 10 feet above the animal, so the falling tag doesn’t have enough time to shift on its orientation.

Rogan said deploying the tags in this way is much less bothersome to the whales then the old pole-tagging method. “It’s certainly really important for us to monitor the behavior of the whales and how our activities are impacting the whales,” Rogan said. “Sometimes the whale will dive after we drop the tag on it and swim away. Sometimes they roll on their side to look up. I’d say for the most part, maybe 70 to 80 percent of the time, we see no reaction and the whale does not respond in any way that we can discern.”

However, these reactions are fairly mild, compared with those exhibited by animals tagged by the pole method, he said. “The boat is very loud … and potentially that acoustic disturbance is the main stressor on the whale. And you’re almost acting like a predator, right? You’re getting really close to that whale with a boat, chasing it down and the animals didn’t like it. So, they often exhibited quite strong reactions to the tagging procedure from the bow.”

Since developing the drone tagging system, Ocean Alliance’s services have been in high demand among other conservation groups and governmental agencies, wanting to learn how to adopt the technology for their own uses.

“At the moment, we’re actually focusing less on our own research programs and really just collaborating a lot with different researchers around the world, particularly when there’s an enormous demand and need for this data,” Rogan said. Last year, the organization worked with the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on a program to deploy tags on North Atlantic right whales, one of the most endangered whales on the planet.

Although the drone tagging program is in its infancy, the organization has already traveled around the world on research and tagging expeditions. Last year, the group returned to Mexico, where it conducted its first drone tagging field testing experiments. More recently, in December, the Ocean Alliance team traveled to the Middle East to deploy tags on a critically endangered population of Arabian Sea humpback whales off the coast of Oman. Plans this year call for tagging expeditions in waters off the coasts of Hawaii, Canada and New England, near the organization’s home base.

Rogan said the drone tagging program has been instrumental in helping Ocean Alliance to achieve its ultimate goal of preserving whale species for future generations. “It’s not just a science and research tool, but it’s very good for conservation as well. It’s helping us better understand these whales in ways that helps us to better protect them,” he said.

Read more:

Jim Magill is a Houston-based writer with almost a quarter-century of experience covering technical and economic developments in the oil and gas industry. After retiring in December 2019 as a senior editor with S&P Global Platts, Jim began writing about emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, robots and drones, and the ways in which they’re contributing to our society. In addition to DroneLife, Jim is a contributor to Forbes.com and his work has appeared in the Houston Chronicle, U.S. News & World Report, and Unmanned Systems, a publication of the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International.

Jim Magill is a Houston-based writer with almost a quarter-century of experience covering technical and economic developments in the oil and gas industry. After retiring in December 2019 as a senior editor with S&P Global Platts, Jim began writing about emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, robots and drones, and the ways in which they’re contributing to our society. In addition to DroneLife, Jim is a contributor to Forbes.com and his work has appeared in the Houston Chronicle, U.S. News & World Report, and Unmanned Systems, a publication of the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International.

Miriam McNabb is the Editor-in-Chief of DRONELIFE and CEO of JobForDrones, a professional drone services marketplace, and a fascinated observer of the emerging drone industry and the regulatory environment for drones. Miriam has penned over 3,000 articles focused on the commercial drone space and is an international speaker and recognized figure in the industry. Miriam has a degree from the University of Chicago and over 20 years of experience in high tech sales and marketing for new technologies.

For drone industry consulting or writing, Email Miriam.

TWITTER:@spaldingbarker

Subscribe to DroneLife here.